This Thanksgiving I served as an international election observer in Tegucigalpa, Honduras. I entered the Central American country hoping to support democracy and see Honduras first-hand. I left the country humbled to my core because the experience changed my worldview.

I struggled to write about my brief experience in a way that would do justice to the people, the country, and the experience. I feel a responsibility to share some of the impacts of U.S. influence on Honduras; I fear I may never come close, but I have to try. I have immense gratitude for my delegation, the organizers, and the people of Honduras. I am so grateful for this opportunity to serve. A very smart person in my group advised me that I can’t go wrong if I just write what I saw.

Housekeeping: All quotes are my best understanding of rough, real-time translations from Spanish to English. Special thanks to my new friends, Amelia, Aura, Burke, Carla, Celene, Jhonathan, Jésus, José Luis, Karen, Leo, Lucia, Phil, Sherilyn, Sneh and everyone else who helped me before, during and after the trip. Apologies for any errors, for which the responsibility is solely mine. All opinions expressed here are my own and are not affiliated with any organizations, individuals or causes mentioned.

Ch. 1 – Honduras es todas estas cosas. (Honduras is all these things.)

Headlines about Honduras in the U.S. shout of gang violence, drug trafficking, extreme poverty, back-to-back hurricanes that devastated the country, and climate change destroying livelihoods. Honduras is part of the infamous Central American “Northern Triangle,” alongside Guatemala and El Salvador, which all have historically high rates of violent deaths.

Yes, all of these things are true. But they’re hardly all that’s true about Honduras.

In isolation, these brief captions capture only a faint fraction of a picture of the Honduran people, without history, culture, context, or compassion. Reality is far nearer, far more nuanced, and far more relatable than most people know.

Americans commonly voice concern about migrants from Honduras and other Central American countries arriving at the U.S. border on foot in massive caravans. Migrants are often portrayed as other people, from other places, with other problems, and thus – other. However, my experience in Honduras revealed to me the numerous parallels that exist between our two countries, and how U.S. choices have impacted the fate of Honduras for generations. We are inextricably intertwined.

The Honduras I witnessed was a paradox. At times it was heartbreaking and raw. It was also strong, powerful, and beautiful. I saw a Honduran political and economic system rife with fraud, corruption, bribery, and human rights violations. I also saw a Honduras rich with ancient Mayan history, and a modern cultural tapestry woven from threads of at least seven indigenous peoples, Afro-Hondurans like the Garifuna, and Catalan descent from the gold-driven Spanish colonization in the 16th century. Nearly 60 percent of the country’s 10 million people now live in poverty, and the country is plagued by authoritarian politicians funneling critical aid away from the basic survival needs of its people. But then, I witnessed the enormous natural beauty and bounty of the country and the empowerment, resilience, and hope of the Honduran people.

Honduras is all these things and so much more.

Our delegation of accompaniers moved throughout the city of Tegucigalpa, and throughout other regions of the country like Colón, Choluteca and Copán, observing and listening to the Honduran people as they engaged in the democratic process. We heard many different stories and experiences, from the angry to the joyful to the tragic. But one saying appeared again and again, regardless of party, past, or position.

“Los hondureños quieren paz.”

“Hondurans want peace.”

As in the U.S., the people have a right to cast their votes in a trusted democratic election, free from fraud, corruption, intimidation, and violence. Whether the Honduran government honors its contract with the Honduran people affects us all. By observing and reporting upon their democratic process, I hope that it will draw international attention to hold Honduran government officials accountable to respect the will of the Honduran people. I hope sharing my experience will cause you to reconsider what you know about Honduras, and pay attention to what’s happening in the Central American region.

Ch. 2 – La delegación. (The delegation.)

I met my first observer colleague from the delegation, Sneh, at the Houston airport. As we boarded the plane, he told me the entrance into Tegucigalpa is one of the deadliest runways in the world and pilots require special training to be capable of landing it. Locals reportedly watch the landings and applaud when the wheels safely touch down. I wonder if they applauded ours.

While our growing group of observers waited in the customs line at Toncontín International Airport, I learned that what was originally slated to be a 50-person international delegation of election observers ballooned into nearly 500 observers flying in from around the world. Our hotel would accommodate about 25 U.S. delegates and 25 more from Mexico City. Delegation members included human rights activists, freelance journalists, photographers, long-time supporters of Latin American solidarity, and general volunteers like me.

The first few days were essential to building relationships so we could communicate and operate as a unit. Several people knew each other from prior activations, but just as many were entirely new. The first night, we all met for a dinner of tortillas, refried beans, cuajada cheese, aguacate (avocado) and plantains at the outdoor cafeteria of the Hotel Alameda, which would serve as our delegation’s home base in Tegucigalpa for the rest of the trip.

To combat the kinds of fraud seen in the 2017 Honduran elections, the lean crew at Centro de Estudio para la Democracia (CESPAD) coordinated a massive observation effort. Partnering with other organizations and activists, they arranged for everything from transportation to safety to training. During our first several days in-country we received background from the founder of CESPAD about the context of the elections.

We walked through the required forms together to prepare for documenting our observations on the ground. Our delegation would observe in nine of the 13 departments in the country, selected because they posed a high risk of experiencing fraud, organized crime, drug trafficking, or high social and environmental impact from the outcome of the vote. We would observe the arrival of electoral boxes, or maletas, containing voter rolls and credentials, among other items. Under no circumstances were we to intervene with the proceeding of the vote, only to use forms to mark our observances and report any human rights violations we observed.

We attended press conferences where representatives from our international delegation articulated the purpose behind our mission, and a shared international aim of fair and peaceful elections in Honduras.

We met with representatives of multiple leading political parties, and shared concerns about the potential for human rights violations during the election process with the office of the United Nations High Commissioner of Human Rights.

We met two of the pro bono attorneys representing the Guapinol River Water Defenders, a group of eight locals unlawfully imprisoned since 2019 for establishing an encampment for 88 days to protest a mining project at Carlos Escaleras National Park in Tocoa. The project threatened to contaminate the primary water sources for an estimated 42,000 inhabitants. The Los Pinares mining company behind the project is owned by some of the most wealthy and powerful families in Honduras. Americans should be aware that the mine is backed by companies like North Carolina-based Nucor, the leading provider of steel in the U.S., according to a multinational investigation reported by Univision.

We also met briefly with deposed president Manuel “Mel” Zelaya, an interesting pre-election perspective considering his history. Zelaya was ousted from office by force in a military coup d’etat in 2009 led by Partido Nacional (the party of sitting president Juan Orlando Hernandez, elected in 2013 and re-elected in the fraud-laden 2017 elections). The coup was backed by Hillary Clinton during her tenure as the Secretary of State in the Obama administration.

“Politicians speak about democracy, principles, values of society,” Zelaya told us. “We have to measure politicians by their actions, not their words.”

“Politicians speak about democracy, principles, values of society. We have to measure politicians by their actions, not their words.”

Manuel “Mel” Zelaya, Deposed President of Honduras

Whether you align with his politics or question his motives, Zelaya has a point. Fortunately, the election observation process is one such way to measure politicians and create transparency and accountability for their actions.

“I am a critic of the system, part of the opposition, so I specialize in studying the weaknesses and the strengths of the process,” Zelaya told us. “I have trust in the Honduran people. They want peace. They respect the general elections.”

The day before the vote, some of our colleagues departed for other parts of the country. My group remained in Tegucigalpa to observe polling sites in the capital. Donning our international observer vests, we visited facilities to be used as voting centers the next day – a small office building, a large gymnasium, a local elementary school.

We spoke with the soldiers on duty guarding the incoming maletas, took note of party propaganda near the voting centers, and observed the state of the facilities for reliable electricity and lights, and internet connectivity to transmit the preliminary results. Keep in mind, many education centers in Honduras suffered great damage from the hurricanes, some were left with neither roof nor walls.

From these sites, we selected the ones where we would spend time the following day. My group chose an elementary school at Suyapa, a working-class neighborhood to the east of the capital, the Centro de Educación Básica Monseñor Jacobo Cáceres Ávila. We passed the enormous Santuario Nacional and Basílica that signals arrival at Suyapa, an area reportedly controlled by the M18 gang.

Two soldiers allowed us to pass through the bright green gate into the schoolyard. The stone and cinder block courtyard walls were painted in bright, child-friendly colors like orange, green and blue. Throughout the yard were concrete picnic tables, and tires painted and recycled into planters.

A knowledgeable caretaker walked us through the classrooms and showed us how it would operate the next day. The building had a dozen aulas, or classrooms, each of which would process about 300 of the local voters, so the site would serve between 3,000 and 3,500 voters in total. The group felt this would be the best place to spend our time on voting day.

Ch. 3 – Los hondureños quieren paz. (Hondurans want peace.)

Sunday morning the delegation was alert and excited to get to work. The polls had hardly opened and we were still eating breakfast when parties started claiming false victory. Every news network crowded the leading candidates with cameras as they cast their votes in their local communities.

En route to Suyapa, businesses were boarding up windows in case they saw a repeat of 2017 post-election protests. The uphill drive is precarious with our large van, yet our expert driver, Julio, navigated the tight squeezes and bumpy road with ease. Outside, street vendors sold fruit juices and cartons of colorful produce, and women patted dough between their hands into rounds, then tossed them onto hot grills with their fingertips.

We spent most of our time at Suyapa and found it to be well-managed. Though there were some questions about the arrival of the Transmisión de Resultados Electorales Preliminares (TREP), the voting process appeared relatively smooth. Of the irregularities we documented, few seemed to be obvious violations.

We surveyed the facilities and spoke to the committees in the aulas to verify credentials. In one aula, we learned that the committee members each represented a different top party, but have known each other all their lives from living in the same community.

We were responsible for observing all of the key actors that make election day function, from the armed forces managing entry to the voting sites, to the committees at the voting tables in the aulas, to the behavior of the voters themselves. We looked for appropriate credentials, critical items needed to process the vote and transmit the results, and how well their biometric fingerprint readers worked. We watched the process throughout the day for things like long lines, potential fraud or intimidation attempts, access and accommodations for people with special needs, start and end times, closing procedures, how the legal process was followed, observations of the interior and exterior of voting centers, and the preliminary vote count to be transmitted. Along with some basic information for each site, we were to document any irregularities or violations we observed and file them. For example, our teammates around the country reported many sites did not receive the TREP machines on time, or in some cases at all.

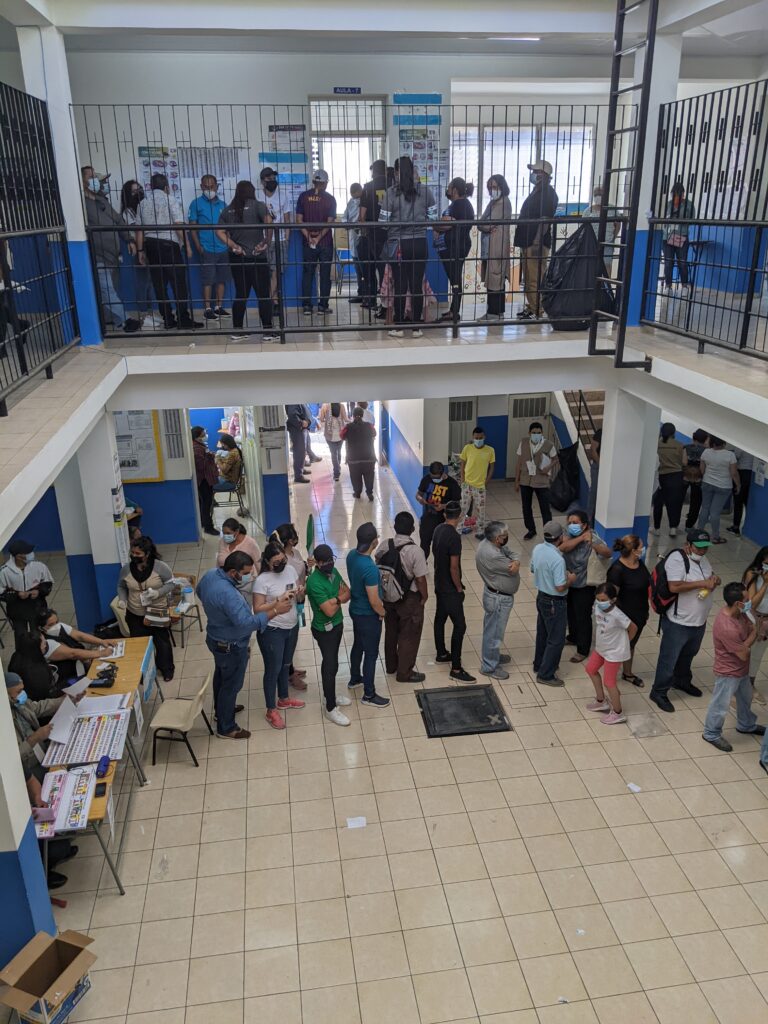

We heard reports of exceedingly long lines at Escuela República de Panamá in the Buenos Aires neighborhood so we hopped in the van and headed that way to join up with observers working the school. When we arrived, the streets were congested with locals grilling and celebrating in the street and our van had to park around the block. Walking to the voting center, we turned the corner and saw the sun beating down on lines of voters hundreds and hundreds of people long.

Tension was high as the line swelled and surged in the front.I it appeared the policía posted at the gate were not consistently admitting voters to the center. Some reported seeing an uncredentialed Partido Nacional supporter illegally refusing entry to voters.

At one point, the crowding and confusion became so intense that a yellow rope was passed for voters to hold to force single-file lines. It seemed to quell some of the frustration in the crowd.

All were masked to prevent the spread of COVID (two days after we arrived in Honduras, the World Health Organization declared Omicron a variant of concern). But inside the building was noisy and crowded, with lines of voters streaming outside each classroom and for blocks and blocks out the door. By midday, the bathrooms were overflowing and unsanitary, adding to the frustration of the voters.

A fellow observer walked with me through the exterior lines to photograph and document. We walked, and we walked, and we walked. Many came prepared with shade umbrellas. I asked how long they had been waiting – several said more than two hours in line, and I estimate they had one to two more to go.

And yet, despite all obstacles, Hondurans showed up to vote. They waited for hours in the lines. With determination, they persisted through the obstacles. In the pursuit of peace and prosperity for their country, nothing was going to stop them. Almost 3.6 million people, 69% of registered voters in Honduras, cast their ballots on this historic day.

Polls are supposed to close at 5 p.m., so my group went back to the Suyapa site to be inside the aulas when the doors closed to observe the count. The committee moved quickly to prepare the room for the count, rearranging chairs to observe the ballot count, posting count trackers on the wall, and stamping and validating paperwork. The Secretary pulled each large, colorful ballot out of the box one at a time, announced the vote cast, and the President captured the tally on the wall, while the other committee members watched and kept count independently. The three known party leaders – Libre, Partido Nacional, and Liberal – took the lion’s share of the vote. Only a small handful of the other 14 candidates on the presidential ballot got even one or two votes.

In the middle of the municipal vote count, we all received a surprise text message from our organizations that we were to stop observing at 7 p.m. and depart immediately for our hotel and stay in for the night. We wouldn’t be able to finish observing the count. Once in the van, I scrolled my phone looking for facts among rumors about Partido Nacional claiming victory and calling for a march in the streets and Libre claiming victory and calling for a press conference.

We watched the results roll in on the TVs at the outside cafeteria at the hotel. As of 8 p.m., with 16 percent of TREP results reported, the CNE said leftist Libre party candidate Xiomara Castro led with more than 50 percent of the vote. Late into the night, people celebrated in the street at Castro’s campaign headquarters, dancing, chanting and waving their red Libre flags.

While more than 80 percent of the preliminary results had not been received by the CNE yet, a nearly 20-point margin suggested a strong lead that would be difficult to dispute. This was an exciting development, but the presidential, parliamentary and municipal races were all on the ballot. This was only the beginning of what would be weeks of follow-up to get final results. There was still plenty of time for things to go wrong. Votes need to be counted, reported, transported, counted again. A transition of power must occur. Every effort to create accountability and transparency, from national and international observers to the international press, is important to make it challenging and more costly for any actor to violate the will of the people.

Castro has since won the election on her anti-corruption platform and has become the first female president of Honduras, taking office on January 27, 2022. Many believe she is the best chance the country has of building economic stability and strengthening relationships with foreign nations. The outcome of the election echoes the groundswell seen in other Central and South American countries lately.

Understandably, many Hondurans remain skeptical despite the election results. Those of power and influence in Central America seem to find increasingly creative means to suppress every threat of anti-corruption efforts. So we wait, and we watch. Porque Hondureńos quieren paz. Todo el mundo quiere paz.

Ch. 4 – Amor con amor se paga. (Love is repaid with love.)

My fellow election accompaniers from the U.S., Mexico, Sweden, Colombia, and beyond unwound at the Hotel Alameda with beers on the patio on the final night in Honduras. Those of us who stayed in Tegucigalpa and others trickling in from other parts of the country excitedly swapped stories and compared experiences at different voting sites.

With midnight fast approaching and my bed calling, I found myself in a conversation with our Canadian liaison in Honduras and an independent journalist from our U.S. delegation who now lives in Mexico City. I shared that the state of the world, especially since the pandemic began, has launched me into an existential crisis. From gross negligence on climate change to human rights abuses to corrupt politicians fracturing nations, we have seen all of these things before, as far back as our most ancient civilizations. At times it feels like humanity is doomed to repeat itself endlessly for all time because this is just who we are and how we’ve always been.

In a reflective mood, we talked about what brought each of us here, and why of all the places struggling in the world Honduras, in particular, called to them. I asked how they keep going as human rights activists when the volume, speed and difficulty of the world’s problems are overwhelming. One said her curiosity about things she was hearing and learning brought her to Honduras originally to look closer. Once she saw the issues first-hand they were impossible to ignore. She moved to Honduras and has lived there now for more than a decade.

Since becoming more engaged in climate issues and the democratic process, I am increasingly aware of the enormous complexity of the problems we’re working to solve. I am also more aware of the need to stop talking and start taking meaningful action. Perhaps activism only gives us the illusion of control, but I believe in the solutions we are working for, and I see the real impact it has on real people.

“Amor con amor se paga.”

A fellow observer taught me a new phrase in Spanish, “Amor con amor se paga.” Love is repaid with love. Every interaction in Honduras helped mold and reshape my worldview. Each conversation and good-natured attempt to communicate with each other through language barriers, every story I heard from a local during the election, and learning the history of these beautiful people in this beautiful country only strengthened my love for humanity. As for solving these perpetual problems humanity faces, I fear I may never come close. But like finally sharing this story with you in a way that I hope does the experience justice, I suppose I just have to try.

If you would like to learn more about Honduras, important causes in the region, and some of the organizations that contributed to this enormous effort, here are a few places to start:

- Centro de Estudio Para la Democracia (CESPAD) – The vision of the organization is to build a more just, supportive and inclusive democracy in Honduras. Their anti-corruption efforts include information analysis and promoting studies for increased transparency and oversight. They also provide support to movements acting for human rights, the protection of natural resources, and women’s organizations.

- Organización Fraternal Negra Hondureña (OFRANEH) – OFRANEH was founded in 1978 to defend the cultural and territorial rights of the Garifuna people, who arrived in Honduras more than two centuries ago after being expelled from the island of San Vicente. This organization is doing important work to protect the survival of this distinct culture.

- Global Exchange – An international human rights organization dedicated to promoting social, economic and environmental justice around the world.

- Honduras Now Podcast – The Honduras Now Podcast shares human rights stories and connects them to global issues and North American policy.

- Center for Economic Policy & Research (CEPR) – A Washington, D.C.-based organization that provides professional research and public education to promote democratic debate on the most important economic and social issues that affect people’s lives.

Ch. 5 – Epílogo: Sabor local. (Local flavor.)

In the days following the election, we squeezed in a few hours of tourism to see the city and wind down. It was a sweet reprieve from going non-stop since arriving in the capital. Below are a few of the stand-out places we spent a little downtime. This was not a photography trip, but I tried to capture a little of the personality of the area during my time.

El Picacho & Cristo del Picacho

The residents become progressively wealthier driving up this 4,300-foot slope on the north side of Tegucigalpa. Our driver, Freddy, stopped halfway up (and kindly aided as a tripod stand-in for me, like a true pal) to get a few snaps of the city before we crossed through the clouds.

It was misty and brisk with no visibility at the top of El Picacho. We couldn’t see the city below, where we were just minutes before, where the weather was balmy and we didn’t need coats.

Hot cocoa in hand, we walked the foggy, surreal-looking paths on the hill to enjoy the Christmas lights and take some spooky-ethereal photos.

At the top, illuminated in a strange green muted in the fog was the 65-foot tall sculpture of Jesus Cristo atop a 33-foot pedestal, a design from Honduran sculptor Mario Zamora Alcantara.

Plaza de Dolores & Iglesia Los Dolores // Parque Central & Catedral de San Miguel Arcángel

Plaza de Dolores i has decent views of the sunset behind the mountains off the central square and a peek at Cristo del Picacho on the hill. My favorite part was watching a small group of nińos chasing pigeons and each other in front of Iglesia Los Dolores (and our friend Jose Luis getting in on the fun with them).

We also walked a short way to nearby Parque Central and the Catedral de San Miguel Arcàngel. Built in the mid-1700s, it’s is one of the oldest cathedrals in Tegucigalpa. This a bustling commercial area with seemingly endless tiendas. It is a busy shopping district, so follow usual precautions for pickpocketing and mugging.

Valle de Angeles

A colorful area we visited for dinner. We only had a few evening hours there, but it has many features I would love to revisit someday – colonial architecture, local arts and wares, nearby ecotourism opportunities, and the Parque Nacional La Tigra cloud forest and hiking trails.

I experienced car sickness on the winding mountain roads because I came unprepared, but with Lucia’s help, I secured exactly two motion sickness pills from the local pharmacy for the ride home. They cut off the larger package for me with scissors – exactly the amount I needed, no more, no less. (I visited three pharmacies for two different reasons while in Honduras… 100% because of thoughtless mistakes I made while packing.)

Librería Guaymuras

Librería Guaymuras is a small bookshop and cafe in Colonia Palmira. They have a carefully curated selection of Honduran and Latin American work, from classics to philosophy to thought-provoking poetry.

Plaza Entre Barcas Tguz

We gathered the groups at Plaza entre Barcas Tguz on Morazán Boulevard for lunch. The restaurant collective is located near big names like the American Embassy, United Nations and the Consejo Nacional Anticorrupción. There is truly something for everyone at Plaza, a bright and spacious restaurant with outdoor seating, a rope swing, a swimming pool, upbeat music, and all-around good vibes. The menus seemed endless from the numerous food stalls, serving from a coffee shop to pizza to Peruvian to seafood to juices.